Engaging Culture in the Global Workplace

組織パフォーマンス向上「グローバル・ビジネスリーダー」

異文化のメンバーが揃うだけではグローバル企業とは言えない。

バックグラウンドを理解し、創発的に活かす取り組みが必要である。

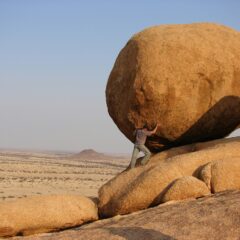

どんなに美辞麗句を並べても、たしかに文化間には壁がある。

だがその壁を足場として、更なる高みを目指すこともできる。

グローバル企業ならではのこの機会を、

すでに十分に活かしている企業はどの程度あるだろうか。

今回は、様々なメンバーで構成されるグローバル企業において、

マルチカルチャーを最大限に活かす方法について考える。

※本コラムは英語で執筆いたしました。ご了承ください。

■Engaging Culture in the Global Workplace

Culture surrounds us, influencing how we see the world and how we interact with it. However, when was the last time you were conscious of your own culture? We usually become conscious of culture when dealing with individuals with a different cultural background. One example that many of us have experienced is when working with people from other countries. In such interactions, the apparent differences make us conscious of language and communication styles, as well as culturally specific behaviors.

The most common response to intercultural interactions is to focus on how different the person from the other culture is, rather than highlight our own cultural peculiarities. We take our own culture for granted – as a constant; we are “taught” our culture through an informal and formal education from birth (with the goal of becoming “cultured” mature individuals).

記事全文をご覧いただくには、メルマガ会員登録(無料)が必要です。

是非、この機会に、メルマガ会員登録をお願い致します。

メルマガ会員登録はこちらです。

会員の方は以下よりログインください。